Boardroom Gap: Companies with More Women in Leadership Perform Better (February 2018, Grank Welker)4/16/2018 Jennifer Conrad didn't have high expectations when she interviewed for a management position at the Leominster headquarters for Fidelity Bank. After all, she was seven-and-a-half-months pregnant.

"I felt like it was such a wasted effort," Conrad said. But "when I stepped out of the bank that day, I said, 'I need to be here.'" She was hired. And a decade later, Conrad, Fidelity Bank's senior vice president and senior cash management officer, serves as an example of a company's culture prioritizing having women in executive positions in equal numbers as men. "She was a very talented person and culturally aligned with how we treat our clients," said Ed Manzi, the Fidelity Bank CEO who hired Conrad and still leads the 10-branch bank. "It just seemed like the right thing to do." With nine women among its top 16 executives, Fidelity Bank is an outlier in the Central Massachusetts business community, as only four of the 42 local for-profit companies examined by WBJ had at least 40 percent women among their senior executives and board members. Fidelity Bank has seen its total deposits more than double in a decade to $659 million in 2016, and in the past year has grown through acquisitions of Barre Savings Bank and Colonial Co-operative Bank in Gardner. This type of financial success is a common thread among businesses with greater gender diversity in their leadership. Companies with women in at least 15 percent of senior management positions have 18-percent more profits than companies where women comprise less than 10 percent of those seats, according to a 2016 study by Swiss multinational financial institution Credit Suisse. The best performance was shown in companies where women make up half of senior leadership positions. "You don't get a diverse lens of what's happening inside and outside your company" without diversity, said Susan Adams, a Bentley University professor who's conducted research for the women advocacy group The Boston Club. "Women live different lives than men," Adams said. "They can see things differently." Woman-led profitsCompanies with women in the top leadership position (i.e. CEOs) were shown in the Credit Suisse study to perform better than those led by men, with 19-percent better profits. Among the 75 Central Massachusetts business organizations – including nonprofits – studied by WBJ, only nine led led by a woman, and none of those were public companies. One of the most recent female publiccompany CEOs in Central Massachusetts was Carol Meyrowitz, who led TJX Cos. from 2007 to 2016. The Framingham- and Marlborough-based owner of retail chains Marshalls, T.J.Maxx and HomeGoods touts relatively high levels of women throughout the business. Globally, 77 percent of TJX's workforce is female, as are 51 percent of assistant vice presidents. In the past three years, women at TJX have earned 51 percent of promotions into senior vice president roles, 40 percent of promotions into vice president roles, and 58 percent of promotions into assistant vice president roles. "At the board level and throughout the TJX organization, women are an important part of our workforce and represent an increasing percentage of our leadership team," Meyrowitz said in a statement. TJX has been a force in retail at a time when many of its competitors have struggled against big box stores and online retailers like Amazon. From the budget year Meyrowitz's CEO term began through the latest budget year, the company's profit rose 161 percent to $2.3 billion, sales jumped 69 percent to $30.9 billion, and the store count rose by 51 percent to more than 3,800. Meyrowitz said achieving goals at the company "relies to a great degree on our ability to continuously develop our next generation of leaders." Female CEOs = gender diversityFemale-led companies have been found to have better gender diversity throughout their ranks, according to a 2017 report by Chicago-based executive leadership consulting firm Spencer Stuart. At female-led American businesses, 33 percent of directors are female. At male-led firms, that rate is 22 percent. In Central Massachusetts, out of the 75 institutions examined by WBJ, the nine led by women have better records of appointing women to boards and executive offices. Their rate for boards is 43 percent, compared to 33 percent among all the organizations examined. Among executives, the rate is 57 percent at female-led entities compared to 36 percent among all. Female business leaders also help companies in intangible ways. Los Angeles-based executive recruiting firm Korn Ferry found last year in talking to 57 women CEOs at large national companies, female CEOs are more likely than male CEOs to be motivated by a sense of purpose and a belief their company could have a positive effect on the community and its employees. New York City-based investment research firm MSCI in a 2015 study found fewer instances of governance-related controversies such as cases of fraud and shareholder battles at companies with better gender diversity. Manzi, Fidelity Bank's CEO since 1997, said gender equality has never explicitly been the bank's objective. "We didn't target a number," he said, adding of the qualified candidates the bank has chosen, "it just so happens that a lot of them are women." On one wall in a Fidelity Bank meeting room is a message illustrating the bank's priorities with employees: "If you value the differences in people, the differences will provide value." Female-inclusive firms remain the exceptionOf Central Massachusetts's 17 public companies, women make up only 8 percent of executive positions. Twelve of the 17 companies don't have a female senior executive, and half of those don't have a female board member. "Biases and misconceptions continue to linger," said Danna Greenberg, a professor of organizational behavior at Babson College in Wellesley. Female candidates generally need to push for themselves for consideration more than a man does, Greenberg said, and a woman who might be seen as pushy could cause a different reaction than a man would. "Women need to figure out much earlier in their career how they balance that pushback from being a strong self-advocate," Greenberg said. Women held fewer high-level positions decades ago because they were less likely to have college degrees, but that's changed. Women make up a higher percentage of college graduates than ever, outnumbering men for the first time in 2014, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. "They're very highly educated, which has changed," Adams said of female candidates for high-level jobs. "You couldn't say that 20 years ago. You probably couldn't even say that 15 years ago." At Fidelity Bank, Conrad said she's seen an environment not typical in finance. "In my 20 years in banking, I hate to use this term, but it can be seen as a boys' club," she said. "It's so refreshing to go to chamber events with more women representing companies. I'd like to see more. Who wouldn't?" CORRECTION: This story has been changed to reflect that it was Fidelity Bank's deposits, not assets, that rose to $659 million.

1 Comment

I have spent many hours talking with colleagues in international development about how to tear down the barriers that block women’s progress around the world. Now, we’re confronting the fact that every sector, including our own, has a serious problem with sexual harassment and violence. The norms that allow these abuses are the same ones that disempower the poorest women, and only when they are dismantled across the globe will all women and girls be able to lead the lives they want.

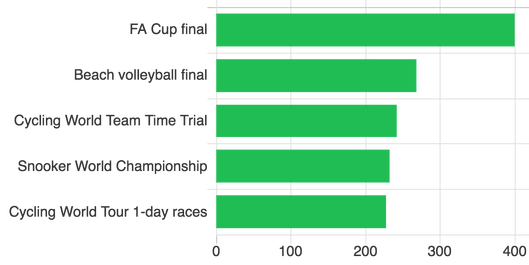

Practically speaking, though, what can a philanthropic organization like ours do to promote a goal—equality everywhere—that’s impossibly large? We’ve been investing in women’s health for a long time and seen significant progress. But as I spend more time visiting communities and meeting people around the world, I am convinced that we’ll never reach our goals if we don’t also address the systematic way that women and girls are undervalued. With a new focus on women’s economic empowerment, connecting women to markets, making sure they have access to financial services, and empowering them to help themselves, we aim to help tear down the barriers that keep half the world from leading a full life. We’ll spend $170 million over the next four years to help women exercise their economic power, which the evidence suggests is among the most promising entry points for gender equality. Simply put when money flows into the hands of women who have the authority to use it, everything changes. First, their families benefit. One in three married women in the poorest countries have no say over major household purchases. Research shows, however, that women are much more likely than men to buy things that set their families on a pathway out of poverty, like nutritious food, health care, and education. In Niger, for example, when women had more financial autonomy, their families ate more meat and fish. One of the most astonishing statistics I’ve seen is that when a mother has control over her family’s money, her children are 20% more likely to survive. Second, everyone starts to re-think the part women can play in their own communities. A recent study in India found that merely owning and using a bank account led women to work outside the home more. As a result, they earned more money, but they also changed men’s perception of them. By defying a social norm that confined them inside, they started to change it. Women acting on their own can do what all the philanthropic organizations in the world can never accomplish: change the unwritten rule that women are lesser than men. Our role, as we see it, is to make targeted investments that give women the opportunity to write new rules. First, our new gender equality strategy will seek to link women to markets. Hundreds of millions of women help run small farms across Africa and Asia, raising crops and livestock, but in most cases, they do so without knowing what is a fair price for their products. We want to help them overcome this barrier and prosper from their labor. To do so, we’ll support women farmers as they organize in collectives that aggregate produce from small farms and sell it to buyers at a fair price and, where possible, use mobile phone applications that provide real-time price information. We also want more women to use digital bank accounts. Many governments send welfare or safety net payments to low-income families, but this money is usually controlled by men. We will work on systems in eight countries, including India, Pakistan and Tanzania, to deposit it into accounts controlled by women. Finally, we’ll support self-help groups where women and girls teach one another about everything from launching a small business to raising healthy children—and reimagine their standing in society. In India, the more than 75 million women who already belong to such groups have proven a force for real progress. We want younger girls to have the same opportunity. During adolescence, parents place more restrictions on their daughters, and girls’ range of movement shrinks—in South Africa, for example, by more than half. Self-help groups can widen their horizons. I gained a valuable perspective on self-help groups when I spent an afternoon in Jharkhand, India, with Neelam Bhengra. She joined a group to learn how to increase the yields on her farm. But gradually, she organized the members to advocate for themselves with local government. “If I’m alone, I can’t do anything,” she told me. But with the support of her group, she said, “I will keep fighting for women until I die.” Neelam is a force for generations to come. She told me all about her children, who were going to school and planning for a future Neelam herself never imagined. The data says that their children, Neelam’s grandchildren, will be even more healthy–and more prosperous. We want to help more Neelams find their voice, seize opportunities, and change their world—and their children’s world—into what they dream it can be. In the ranking of the 100 highest-paid athletes, there is just one woman - tennis star Serena Williams. |

Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed